Seasonal work and the winter push

The rhythm of the seasons has always impacted the human race – in more recent millennia, when to plant, when to harvest. In East Anglia, the harvest brought opportunity for employment to thousands of agricultural labourers for centuries. There was winter work, too, but the workhouse loomed larger for many. Stone picking and digging bush drains might be options, but what if wages were higher elsewhere? What if mechanisation was increasingly used for threshing? What if young men and women could see opportunity elsewhere?

For young, strong men with fewer family ties, especially those with intermittent work who were underemployed or unemployed, there were options. We know about the growth of industry in the north, fruit and hops in Kent, the pull of urban areas, but this post is about a place and a period of history we hear less about. Anyone who has spent time perusing the census enumeration books for Badingham and Cransford will have seen a relatively frequent birthplace appearing by 1901 and 1911: Burton upon Trent.

There’s a very good reason why.

In the late 19th century, several workers from Badingham and Cransford, in common with other ‘Suffolk Jims’, followed the barley. With the harvest out of the way by September, workers could travel the approximately 150 miles to Burton to help with malting the very crop they had gathered. A few months later, they could return home as the barley ripened once again, making the most of the economic opportunities in both places.

This migration wasn’t always a permanent move, or a population turning its back on a rural way of life. But it was a way for people to avoid parish relief and to enjoy better wages than might be had at home throughout the winter.

For this post, I set out to see just how many of my Badingham and Cransford One-Place constituents had confirmed links to Burton upon Trent. I found far more than I imagined, and I’ve ended up with a significant piece of research. It’s been fascinating to see the micro histories of the people and names we might recognise playing out the macro stories of industrialisation, boom and decline, and the ebb and flow between places.

The people in these stories were connected in multiple ways – they were families, communities, and otherwise economically associated. Their networks are shouting from the documentary record in a way I didn’t expect, but in a way that could easily be missed if we were looking at just the occupants of a house, or the direct line of a family tree.

My exploration doesn’t pretend to capture everyone who made the journey from Badingham and Cransford to Burton, nor every season they may have spent there. As genealogists, we are schooled in making robust conclusions, but sometimes we need to build a narrative around the ‘why’ to tell a more interesting story that goes beyond names and dates. A census places a person somewhere, but local history suggests why they were there in that place at that time. What follows is necessarily partial, shaped by what I’ve found in the creation of this post. I offer it as a representative collection of case studies, organised chronologically by arrival in Burton and how that maps to the development and later decline of the brewing industry in the town.

I welcome comments from others who have traced similar paths from this part of Suffolk, so that this shared history can continue to grow in this little part of the internet.

Some context and sources

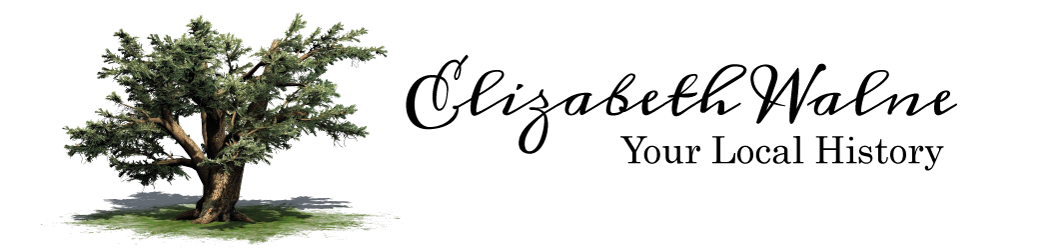

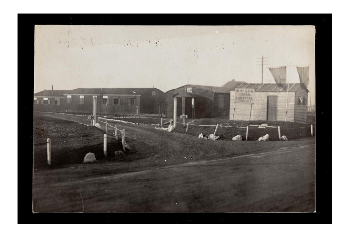

Burton was booming in the late 19th Century, turning out 980,000 barrels of pale ale a year in the mid-1870s vs 70,000 in 1840. Huge names in the industry, such as Bass, Ratcliff & Gretton Ltd and Samuel Allsopp & Sons, needed temporary labour for malting from September to May, fitting nicely outside the months of the home harvest. By the end of the 19th century, Burton had the most extensive beer breweries in the world, supplying as much as a quarter of all the beer in Britain: more than 3,000,000 barrels a year, the brewing of which employed more than half the town’s burgeoning population. This level of production, possible due to a combination of Burton-specific factors, was unique in the UK.

A couple of sources inspired this post. First, appendices from George Ewart Evans’ Where Beards Wag All, which contain lists of East Anglian workers who migrated to Burton, many of them from this area. Second, that most-consulted but endlessly fascinating record collection, the decennial census. There are, it turns out, plenty of people moving between Burton, Badingham and Cransford, identified within census folios simply by dint of their birthplace being different to their home on census night. My subsequent methodology included creating profiles for these men and women, as well as investigating their immediate families, adding plenty of new faces and stories to my online OPS family tree. It must be said that the long-overdue digitisation of Suffolk registers has been a boon in the past couple of weeks, but alas, Badingham’s registers are not yet among them.

In my initial foray into available sources, I had a lovely surprise. An RQG colleague, Carolyn Alderson, has published her Genealogical Investigation of the Suffolk Seasonal Maltster Migration in 19th Century Burton upon Trent in the RQG journal. Carolyn identifies Henry Edwards Junior, born 1815, as the initial catalyst for the seasonal migration. Henry was a maltster, manure and corn merchant from Woodbridge who saw an enormous opportunity for the Woodbridge area to make additional profit from its barley. Advertising in 1858 for ‘young strong able agricultural labourers’, Henry played his part in encouraging Suffolk-Burton links…and word spread among local people.

I think that ‘spreading of the word’ was vital, and goes a long way to explaining why Suffolk made up such a large proportion of the seasonal labour in Burton. If your employer has openings, and you have family and friends you can recommend, then you send word, or at least, next year when the brewery agent comes to Framlingham Crown, you take them with you. If you made a relatively good living in Burton in 1878 vs clearing ditches on the days the sun shone in 1877, then you return in 1879 – and you bring your younger brother and perhaps even your new wife.

Not yet here for the beer (1841-1861)

The first Badingham and Cransford-born workers in Burton predate the beer boom. It’s important to note that because we’re going back to 1841 here, the date of the census matters. From 1851-1911, the census was taken in late March or early April, but in 1841, it was taken in June. This means that seasonal labourers might have been back in Suffolk and thus missing from the returns taken in Burton that year. However, beer production in Burton was still relatively low.

Our first case studies are all women, not the enterprising ‘strong able agricultural workers’ – and most likely young men – Henry Edwards’ ad might have evoked.

First, we meet Harriett, Badingham-born but in Burton for that first commonly-accessible census, the 1841. This is early, and the census reflects this – Harriet was married to George, who wasn’t a maltster but a shoemaker in both 1841 and 1851.

It’s possible this is Harriet Wood(s), baptised in Badingham in 1794. There is a marriage in London on 20 December 1835 at St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney, between a widowed George Port and Harriet Wood. For the purposes of this post, this is a circumstantial suggestion, not yet a robust conclusion; that said, the other Harriets baptised in Badingham during a similar period all appear to be accounted for.

Harriet and George seem to have moved to Burton for good; Harriet lived on the market place and died in the town in 1855. As such, Harriet doesn’t fit the narrative of a seasonal worker, or the wife of one. Harriet and George’s lives brought them to the town via London in middle age, but not as a direct consequence of brewing or directly from village life.

Our next women migrants are a pair of sisters, Eliza Ann and Clara Barham, daughters of a Badingham family headed by John and Sarah Barham. Much younger than Harriett, Eliza was baptised on 24 January 1842, and Clara was born in 1855. The Barham family lived near the Bowling Green Inn in 1851. Interestingly, at that time, the head of the household was Sarah, the girls’ mother – a ‘drillman’s wife’. Just where was John? Hold that thought.

Eliza married young, in 1860. Her groom was John Rowe, born in nearby Bramfield. By the time of the 1861 census, the couple were living in Burton where John, too, was a drillman. Eliza had taken six-year-old Clara with her. John was most likely the young, strong, hearty agricultural labouring type that the beer makers were beginning to look for – but just like George Port, he wasn’t a maltster.

Back to John. Sometimes you need to use multiple sites to search census returns to find your man! It turns out there was an earlier Drill Man (sic) in Burton Extra, and sure enough, it was Eliza’s father, John Barham, who was lodging with his brother at a ‘Nail Manufacturer and Beer House Keeper’s’ on Water Road in 1851, while he was missing from Badingham. John’s brother Henry was a drill man too, and over in Stapenhill, there’s yet another Barham, William, with the same trade.

So here’s an example of networks in action, this time, over two generations of the same family – even if it’s not in beer. I think the Barham family were all connected to seed drills – Smyths, which was to become world famous, was based in Peasenhall, busily creating new generations of seed drills right next door to Badingham. Men like the Barhams, many of them from the Peasenhall area, were taking them out into the world, earning money as skilled contractors who could sow faster and more consistently with a new drill than by hand.

I wonder whether, while this Badingham-Burton connection is for a different trade, it nonetheless started to build bonds between the two places. Growing grain naturally leads to malting grain, and the first Barham drillmen would have met landlords and scoped opportunities. Theirs was a big family in a small community back home and they would have returned to Suffolk with intel to share. It’s perhaps telling that in Where Beards Wag All, yet another Barham appears on the Bass, Ratfliff & Gretton Ltd list for the 1926/7 season, indicating that the connection may have stretched and adapted over another generation or two.

The next question becomes whether Eliza and Clara remained in Burton permanently. The answer is no. On every other census, John and Eliza were living locally: Peasenhall, Rendham, and finally Derneford Hall and then Pound Farm at Sweffling, where John rose to become Farm Bailiff. Those early days as a contractor bought him experience and a roof over his head before he could secure better employment at home. Eliza and John, by 1911, were parents of ten surviving children (from a total of eleven); this is a Badingham-Burton family that likely has many descendants today. Clara, too, was a short-term resident of Burton. She later married Frederic Button Roe (sic, no w this time) and lived in Cransford, Peasenhall, and Horham.

When moving to malt became an intentional choice (1870s-1880s)

The railway branch line at Framlingham opened on 1 June 1859, joining the town to the East Suffolk Line just north of Wickham Market at Campsea Ashe. For those looking for employment, this might have made the journey to Burton – and the decision to go – a little easier. The expansion of the railway network certainly boosted Burton’s ability to distribute ale and scale production to meet the increased demand. That increased demand meant more workers, and deliberate migration specifically to malt barley.

Our next case study was living a few doors down from the Barhams in 1861. I don’t think it’s a stretch to imagine Burton being a topic of conversation at the bar at the Bowling Green Inn. Perhaps Arthur Goodchild was enjoying a pint one evening in the mid-1870s, bemoaning his winter prospects, when old man Barham told him there was a good living to be made in malting.

Arthur Goodchild was baptised in Badingham in 1858, and, like so many others in this post, the son of an agricultural labourer. It’s always important to stress that the census is taken only once every ten years, but there is so far no reason to believe that Arthur didn’t spend his childhood in the village between censuses. When he was about 18, he married Rosanna Whincop from neighbouring Peasenhall. Arthur and Rosanna must have left for Burton soon after their marriage because by the time the 1881 census rolled around, they already had two children born in Burton. Maybe Arthur had already been in Burton for a winter season or two before his marriage. Unlike those we’ve met so far, Arthur appeared on the census as a maltster – our first documented.

Networks are again in action here, not just because his neighbours had already been finding work in Burton, but because Arthur himself had already got a lodger – his younger brother John, who didn’t show in the initial searches as his birthplace is noted as ‘Baddington’ (near enough!). For John, his migration to Burton was just the start. While I haven’t researched him in any depth just yet, it looks like he headed to Penge and then Hammersmith before ultimately emigrating to Australia (all while sporting a very handsome moustache!).

For Arthur and Rosanna, it looks like Burton became their home for several years. Again, while we have to remember that the census is a snapshot of one evening, all five of the children with them in 1891 were born in the town, and Rosanna’s widowed mother, Priscilla, was also living with them in Burton, along with a new lodger learning the malting trade from Arthur. The family setup suggests rather more permanence than if Arthur were simply lodging somewhere. By 1891, with brewing reaching its peak, there would definitely have been work to support a whole extended family year-round. What’s more, experienced maltsters hosting lodgers ensured a reliable, sustainable source of new labour for the breweries. That said, the connection with Suffolk remained strong; by 1895, Arthur was back. Sadly, we know this from his death record. He was just 37. Arthur was laid to rest where it all began, in Badingham, on 18 June 1895.

For Rosanna, the future remained Burton, even without Arthur. In 1901, she was working as a charwoman there, supporting her children as a second generation in the town. It was a similar picture in 1911, by which time Herbert and Bertie had followed their father into the trade, and in 1921, when she headed a multigenerational household of coopers and wood turners, including grandchildren. Rosanna never remarried. She died in Burton in 1928.

There is another man from Badingham who first appears in Burton in the 1891 census. This chap is Robert Dunnett, who also appears, as ‘Robert Drumett’, in Appendix One of Where Beards Wag All (‘hired by Bass, Ratcliff & Gretton Ltd for work in Malthouses in Burton-on-Trent, 1890-1891 Season’). Unlike Arthur, we know that Robert was probably, at least initially, a seasonal worker. Robert was among three young maltsters from Suffolk boarding with a family on Waterloo Street on that census night.

Robert had previously lived on eight acres farmed by his father John in Badingham, and came from a large family. We know he came and went from Burton because in 1901 he had returned to Suffolk, living at a property near Stark Naked Farm in Flixton. Robert was at that time a horseman living with a stockman and his family. Without this 1901 record, it might have appeared that Robert had gone to Burton and stayed, because the next we see of him is his marriage to Hephzibah Harriet Bullen back in Burton upon Trent.

Robert’s marriage, taking place in February 1903, would have been during the traditional malting season. Hephzibah was a widow, having previously been married to John Bullen, another East Anglian maltster whom she had married at Stoke Holy Cross in Norfolk before moving to Burton and raising a family. Poor Hephzibah lost Robert and found herself a widow again just a year after their marriage. She later married a third maltster, Tunstall-born Suffolk man Horace Reeve, who worked for Bass Co. It seems Horace and Hephzibah both died in Burton, too. A decision was made, quietly or otherwise, to abandon any seasonal movement and make a permanent life in the town; Horace was still working for Bass in 1921. Hephzibah’s story rather suggests that the men from Norfolk and Suffolk in Burton were part of a smaller community within the whole – was it coincidence that all three of her husbands were from the same area, or evidence that they mixed in similar, smaller, circles? Evans’ recollections might suggest the latter – men in different clothes with different accents to their Staffordshire counterparts, who arrived together on a one-way ticket from their local railway station and stayed together thereafter.

The peak of the pull of the Burton pint (1890s)

By the 1890s, enormous breweries in Burton were well established. Beer was being brewed, yes, but the industrialisation of that process brought with it a whole supporting infrastructure and a growing population. Those people from Badingham and Cransford who first appear in Burton in the 1901 census reflect both brewing and its inherent infrastructure. There is a new diversity to the occupations recorded in the census, and the routes our people take after appearing in Burton.

It was another family affair for the Bakers. Harriet Baker, daughter of William and Sarah, was baptised in Cransford on 23 December 1866 alongside her cousin, Frederick Ife. Both would find themselves in Burton. Harriet moved for work regularly while she was young. Moving from a cottage near Fiddlers Hall, she became a housemaid in Theberton in 1881 and was promoted to cook at a small temperance hotel called ‘Shaftesbury’ in Colchester by 1891.

Perhaps another domestic role took Harriet to Marchington Woodlands in Staffordshire (west of Burton) by the time of her marriage to Alfred Smith in 1896. Alfred was a Staffordshire man born in Silverdale. The birthplaces of their subsequent children suggest they moved to Branston, rapidly growing into Burton, around 1899. Their address of Clay’s Lane in 1901 places them in 19th-century housing that crept along the main road towards the town centre as the town boomed.

Alfred was a carter for a coal and corn merchant. Both of these commodities were vital to Burton’s breweries in the Victorian era. While corn and barley are of course different, a corn merchant would sell both, so that part is obvious. But coal? It turns out that it took between 31 and 85lb of coal to produce a single barrel of beer, depending on the specific processes and equipment available. According to a paper by Nevile in 1906, the coal wasn’t just required for boiling, but for heating liquor for mashing, providing steam for washing casks, and to provide motive power. Alfred was moving the ingredients for a flourishing, coal-fed, Victorian industry. In this endeavour, he was supported by his wife’s Cransford cousins, who were coal miners and railway engine drivers at Newhall, four miles away.

Then we have William Eagle, a young man born in Cransford in 1872 and raised in Culpho – and another agricultural labourer’s son. William’s father, George, remained working for the Hunt family of Culpho for over half a century, his obituary remembering him as strongly religious and exceptionally capable: ‘a thatcher, engine-driver and farm foreman…particularly expert in sowing artificial manures [and] sowing with both hands, so that he did double the amount of work in a day’. I suspect William was not baptised in the village church at Cransford because his family were Baptists; he was by no means the only non-conformist in the parish by this time – the church baptism register is exceptionally quiet in the early 1870s.

William had left the family home by 1891 and married Agnes Sarah Marven in Hendon, Middlesex in 1898. The pair probably remained in London until shortly before 1901 (their daughter, Agnes, was born in Cricklewood). William was not a maltster, but a railway wagon repairer. So, he didn’t follow the barley directly, but like Alfred Smith, he was a vital part of the brewing industry in another way. Burton could only have exported beer as it did with the help of the railways. Without an efficient transport system to distribute it, beer would have remained a locally produced commodity for the most part, instead of production becoming focused in a small area.

It struck me here that Harriet had been working in a temperance hotel and William grew up in a strongly religious household. We don’t know from these records whether they were teetotal, but could it be significant that they were working on the infrastructure side, not in the breweries directly? Evans’ recorded recollections remember Suffolk’s seasonal maltsters as hardworking and hard drinking, singing and dancing through pub after pub. Was it possible to participate in Burton’s economy without endorsing its drink?

A return to rurality?

We move now beyond the zenith of brewing in Burton. The discovery of ‘Burtonisation’ made it possible for companies outside the town to make water resemble Burton’s. Having had more than thirty large-scale breweries in the late 19th century, seventeen remained in Burton in 1911. While these were still a significant source of employment, the micro again reflects the macro in our Badingham and Cransford case studies – by 1911, we see children born in Burton back in Suffolk.

But before we meet those children, we need to revisit the Smiths and the Eagles from the previous section. Did they stay in Burton, or were they affected by the decline in production and profitability?

First, the Smiths. Harriet and Alfred left, but didn’t travel very far; some of their cousins, the Ifes, did remain. While several of the Smiths’ children were born in Burton, the next census, in 1911, places them in Church Broughton, about ten miles north-west, where Alfred was working on his father’s farm. Perhaps there is truth in the suggestion that the industry was a young man’s game; perhaps his family farm just needed him back as farming crept out of depression, and Burton offered diminishing returns. By 1921, Alfred and Harriet were farming on their own account. Harriet’s father had been noted as a pauper back home in Cransford, labouring on another man’s estate when he could. We can hope Harriet felt her efforts had paid off.

As for the Eagles, the family chose Burton as their permanent home, but it wasn’t without change. The 1911 census finds William, now that much older, as a dental mechanic – a ‘working man’s tooth puller’, potentially making teeth to fit as well. There’s a fascinating article on this called ‘Monty, Bring the Blood Can!…’ by Claire Jones if you’d like to learn more. Clearly, this was an occupation that suited William; he was working for Ernest Street Dentist at 75/6 Horninglow Road in 1921 as well. Meanwhile, his daughter and sister-in-law worked at Bass & Co. and Crosse & Blackwell, respectively. Crosse & Blackwell was in the process of opening a factory in a former WWI machine gun factory at this time, representing a new and diversified industry in town – one that would soon after (but not for long) make the famous Branston pickle. William remained a dental mechanic until he retired, passing away in Burton in 1946.

Back to the Hammond children. Arthur, Albert, Rose and Maud were all born to John and Alice Hammond while John was working in Burton. The family (minus Maud, who was by then a live-in servant at The Red House) was at Stone Cottage, Badingham in 1911. The second youngest, Rose, at ten, was the last child born in Burton. The 1901 census must have caught them not long after they returned to Badingham. The family were living on Carrs Hill, not far from Colston Hall. John Hammond was 40 at that time, working as an ‘ordinary farm labourer’. Arthur, Albert, Maud and Rose have all had ‘Lincolnshire’ Burton replaced for Staffordshire – someone perhaps wasn’t sure where it was! Timings are crucial here. Ethel, their eldest, was born in Badingham in 1892, and Rose, the second youngest, in Burton in 1900. The Hammond family could have lived in Burton for nearly nine years without being caught by a census. Potentially, they made the trip each year, but with every child born in Burton, it may have been rather more permanent.

Further research showed that Alice Hammond’s maiden name was Goodchild. Sure enough, she was Arthur Goodchild’s sister. The Goodchild and Hammond cousins must have been in Burton together, even after Arthur Goodchild died. I haven’t gone out of my way to look for connections between people in this post who were seeking work in Burton, but nonetheless, the associations are shouting at us from the documentary record. It makes sense – but those networks still existed in Badingham, too. As fortunes and opportunities in Burton waned, and a few years after Alice lost her brother, the Hammonds came home to Suffolk. It doesn’t look like any of them ever returned.

Closure and conclusion

There is some evidence of continued seasonal migration, even in 1911. Perhaps this was a return to the seasonal migration of the past as permanent moves became less lucrative. Harry (Henry) Hambling, born in Badingham, along with Frederick Briggs from Laxfield, was lodging with the Bennett family, both working as maltsters in April 1911, just as young men from earlier generations had done. For Harry, Burton was a short-term work opportunity; he was back in Badingham to marry on 9 October 1913.

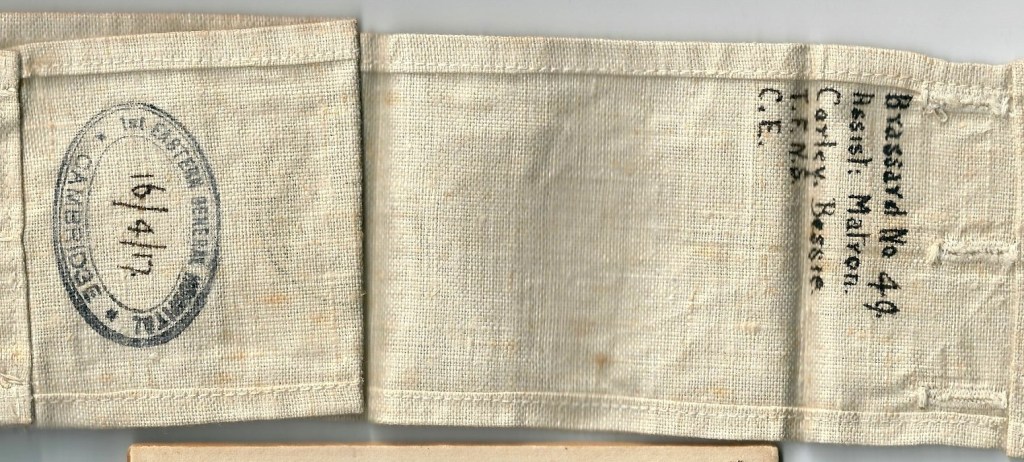

Harry’s generation was the right age to be called to the trenches. Tragically for the Hamblings, he died from his wounds on 9 December 1917. Harry’s wife Florence (nee Ablett), was left behind with two small boys, Harry and Arthur. We are fortunate to have some surviving records for Harry’s war service. His papers show that, when he signed up, he was living at, of all places, Stark Naked Cottage at Flixton – I don’t think this can be a coincidence. Did Harry meet Robert Dunnett, or did other workers in Flixton influence his choice to work in Burton for a season or two? These were families and communities who knew each other well and shared knowledge and experience. There is (so far) no evidence that Florence and Harry went back to Burton after their marriage. Florence married again in 1921, her groom Arthur Pipe, a farmer from Rumburgh.

Harry was perhaps one of the last Badingham men to head off to Burton for the malt. The war took the same young men who migrated for work from the factories and breweries and sent them to Flanders. The war also brought increased restrictions on the trade of alcohol and reduced pub opening times, as well as creating difficulties in sourcing raw ingredients. By the time the war was over, there was no going back and brewery closures continued. Only five breweries were left by 1950. Nevertheless, Burton still brews plenty of beer today. It’s now home to Molson Coors (brewing Carling, Grolsch and Coors). Microbreweries have also seen a resurgence, and are in some cases occupying older brewer premises, see, for example, the Burton Bridge Brewery.

Harry’s story brings the arc of Badingham and Cransford men in Burton to a close. He is a last echo of patterns established over the course of fifty years. There is more work that could be done here to extend the narrative. For example, extending the research to Framlingham, another of my favourite places, quickly finds teenagers Isaac Neeve, Henry Eade, James Walling, George Smith, Herbert Whightman (sic), and Frederick Nesling as potential case studies. Herbert and George were two of no less than six young men from the area lodging in the same house in 1901 – Thomas Flatt (Burgate), Frederick Borrett (Woodbridge), Frederick Bloomfield and Tom Thorpe (both Saxtead) being the others. Similarly to Badingham, by 1911, a significant number of children born in Burton were back in Framlingham.

Badingham-Burton migration is a story of opportunities grasped until such time as the economic and human pull reversed. This New Year, I’ll be raising a glass of IPA and remembering the Badingham and Cransford folk who helped bring it to me.

Endnotes and sources

Full references for each genealogical event can be shared on request. These make for an enormous endnotes section so I have summarised here.

- Census returns for England and Wales, 1851–1911.

- George Ewart Evans, Where Beards Wag All (London: Faber & Faber, 1970), particularly the appendices listing East Anglian workers migrating seasonally to Burton upon Trent.

- Carolyn Alderson, Genealogical Investigation of the Suffolk Seasonal Maltster Migration in 19th Century Burton upon Trent (available: https://www.qualifiedgenealogists.org/ojs/index.php/JGFH/article/view/146/85).

- The Historic England Blog, Burton upon Trent: The Beer Capital of England (available: https://heritagecalling.com/2025/03/27/burton-upon-trent-the-beer-capital-of-england/)

- Nevile, S. O., 1906, Coal consumption in breweries (available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.2050-0416.1906.tb02172.x)

- Claire Jones, “Monty, Bring the Blood Can! Pulling Teeth in Working-Class Lancashire, 1900–48”, (available: https://academic.oup.com/tcbh/article/35/2/223/7684985)

- Parish registers, civil registration records, and local burial records for Badingham, Cransford, and surrounding Suffolk parishes

- Boak, J. & Bailey, R., “From Suffolk to Burton in search of work, c.1880–1931”, Boak & Bailey’s Beer Blog (2019) (available: https://boakandbailey.com/2019/07/suffolk-burton-migration-brewing/)

- Brown, Pete, Hops and Glory: One Man’s Search for the Meaning of Beer (London: Pan Macmillan, 2009). [While not directly used in the creation of this post, this is a book recommendation – I very much enjoyed it!]